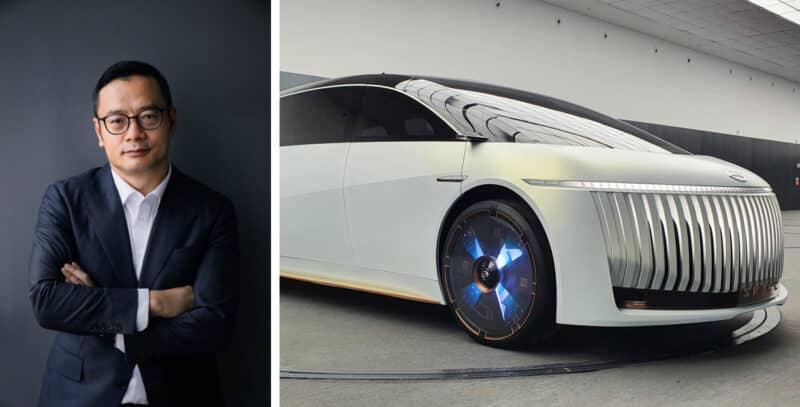

Zhang Fan, GAC’s Head of Design: Discussing the Evolution of Chinese Car Design over 30 Years

Looking at the products of China’s vast and rapidly developing automotive market today, it’s almost impossible to imagine that between 30 and 40 years ago, China’s roads barely contained any cars.

The cars of local brands that existed back then were generally rebadged versions of cars developed elsewhere, a practice that continued up to around a decade ago.

So just what was car design in China 30 years ago, how did it get to this point, and what advantages are there to being so late to the party?

We sat down with GAC Chief Designer, Zhang Fan, the first Chinese designer ever hired at Mercedes-Benz, to get answers to those questions and many more.

This interview has been shortened, and in parts paraphrased, to make a more concise article. You can find the full interview in the video at the bottom.

The early days of a glittering career

As a kid, I would sketch cars for hours. Like any car fan, it was the designs that captured my imagination, but then there was plenty to go on.

For example, my family’s first-gen Renault Megane Scenic. Its endless flexibility inspired me in a million ways how to make a car interior smarter and more practical. Regular trips to the Renault dealership (yes, it was fairly unreliable), also gave me the chance to admire and pull apart some of the design classics of the day, like the Avantime, which I adore to this day.

But what if all I’d had to go off was thousands of bicycles and the odd dignitary passing by in a luxury imported car? What if having for one moment imagined I could design one of these vehicles, I had no way of learning and no route into such a career?

Growing up in China in the 80s, this was essentially the situation Zhang Fan faced.

“I like drawing. I’ve enjoyed drawing stuff ever since I was very, very little,” he begins when I ask him what got him into car design.

He continues: “I always would like to become somebody able to draw and able to connect that with other knowledge, but before university, I didn’t even know there was a profession called car design or even industrial design. That was 30 years ago.”

University beckoned on the horizon and Fan’s desire to turn his passion into something productive led him to Tongji University in Shanghai where there was a major in Industrial Design.

“When I read the description for the first time I found ‘Whoa, that’s something I really would like to do,’” Zhang exclaims, a smile breaking out across his face.

But as anyone who has been to university will know, taking the course on its own is not enough to make you a success, and Fan is quick to stress that his position today is the result of not only hard work and passion but some choice opportunities that presented themselves along the way.

The first such break came in the fourth year of the five-year course, where Fan had the opportunity to meet Klemens Rossnagel, a man who went on to a long design career at VW and Audi, and his wife.

“They were very interested to collaborate with the local university and try to find some young talent,” says Zhang, remembering Volkwagen’s first tentative steps into a market they would go on to dominate in later years.

As part of the work with Rossnagel, Zhang and his classmates were given the opportunity to make several quarter-scale clay models, a first in the Chinese market.

Upon completing the course, Zhang was seemingly no closer to his ultimate goal, and in the interim chose to spend some time with Chinese lecturer, Liu Guanzhong, whose design philosophy inspired Zhang’s inner designer.

“At that time in China there were almost no professional car designers and no proper car design profession, so I was wondering what I’m going to become after my graduation,” he says. Further education seemed the best bet and it was here that another well-timed opportunity presented itself.

Much like Harvard to Americans and Oxford to the British, Tsinghua University in Beijing is the one education institution all Chinese students aspire to attend and, by a stroke of fortune, the smaller school Zhang was attending was adopted by the prestigious school.

There, with the might of Tsinghua behind him, Zhang got the chance to participate in an international design competition hosted by Pforzheim University and Auto Motor und Sport magazine. The jury panel, flush with famous German car designers, would afford one more decisive opportunity to Zhang.

Despite feeling considerably out of his depth among the young designers in the competition, Zhang had unknowingly caught the eye of then second in command at Mercedes-Benz design, Murat Gunak.

“Right after the presentation he approached me at coffee time and asked what would I like to do after graduation. I said, if possible, I would like to become a car designer, but to be honest I didn’t really mean it because there was no opportunity as far as I knew, but he actually asked if I would ever imagine coming abroad to become a car designer.”

The rest is history. After a year-long wait to process his move to Europe, Zhang became the first ever Chinese student hired from China directly to Mercedes-Benz.

“I consider myself lucky,” he says humbly, thankful that Gunak had spotted talent in his ideas if not in his design itself.

“When you’re drowning, you have no choice but to fight”

Once within the prestigious confines of Mercedes-Benz’s design team, Zhang and his fellow graduates had two years to impress and secure a full-time contract. But as Zhang himself confesses, time was not on his side and self-doubt was an issue he had to contend with.

“If you just talk about the professional skills and knowledge, I was not qualified,” he said, “but there must be something Mr. Gunak saw in me that could be beneficial for Mercedes.”

Recognizing that the only way to save himself from “drowning” was to “fight” for the chance he’d been handed, Zhang set to work proving he had the right attitude first and foremost. He recalls using “every means I could to show my ability, for example, even for some kind of ‘dirty’ jobs, like doing wheels. I could produce 30 (a week), maybe 10 times what they (my fellow graduates) could create.”

It was a year and a half into his time before Zhang got his first shot at a quarter-scale clay model but his work ethic and continuous self-improvement impressed his team leader enough to mean that Zhang graduated into the full-time position. He humbly concedes that maybe others at the time were more skilled than he was, but his background and different way of thinking were also able to bring elements that they could not.

“For a design organization, you do need a certain kind of diversity in terms of the working style and also the perception of design. I was lucky I was a different one, and I also worked hard to prove that I was able to provide good ideas.”

This alternative and unburdened view of what cars should be was a particularly lucrative commodity at a time when China was just starting to open up and was seen as a market of untapped potential for Western car brands. It was precisely for this reason that one of Zhang’s senior managers was looking to collaborate with Chinese students, precisely because they “didn’t know how to drive” and “didn’t have much knowledge about cars, so therefore whatever they came out (with) could be some new inspiration for designers.”

Nowadays, we’re seeing this new way of thinking playing out in real-time with the rise of China’s electric car market and the development of a completely new design language previously unseen in what was once considered a copycat market.

“We’re traveling lightweight”, says Zhang, referring to Chinese design and its newfound self-confidence and the country’s enormous push to lead the global EV market. “We’re easy to turn around, and we’re also trying to catch up with the new wave.”

Homegrown Design Leadership

Before sitting down with Zhang Fan, I’d just been given a tour of GAC’s newly opened Design Centre in Guangzhou. The team had recently moved from its older building across the road into a flashy new space filled with adventurous concept cars and a large display area where the brand showcases its history, technology, products and design inspirations.

The very presence of a design center, let alone concept cars and a technology showcase, is a testament to the advance in China’s car industry. Such areas could never have existed back when Zhang was first studying to make design his career, but today they’re presented with the confidence of an industry that finally feels it can compete and lead on the big stage.

It has been quite a journey to reach this point, and over 12 years as GAC’s Head of Design, Zhang has seen plenty of change. Switching the bright lights of one of the world’s most famous brands to a relatively modest Chinese automaker was his opportunity to make it happen.

“(At Mercedes) I was mainly working as a designer. At GAC I could make a great career to be influential to the whole industry. I started with 26 people in my hand back in 2011 and now we have over 400 people around the world located in four major cities in three different countries.”

As China’s car design industry tackles the new challenges in mobility, such as autonomous driving, sustainability and digital technology, Zhang’s team must now do so much more than merely design cars, but the new wave of hungry talent is ready.

“Some of them they are very, very young but they are fearless, they’re very passionate, they have all the knowledge about the new technologies, about new design trends,” says Zhang with pride. “I will try to blend all those kinds of different power together.”

Zhang is now a veteran in the field yet his vision for how cars are changing, and what cars can be, still draws on that freshness of thinking from a young Chinese car market. You can see this reflected across the field of new Chinese EVs, where cars are increasingly becoming lifestyle spaces rather than merely “sexy driving machines” as Zhang recalls cars being when he worked for Mercedes-Benz.

“We are witnessing the changing of the car industry which has been caused by the breakthrough of certain technology, this electrification, smart driving, and the internet technology. (We believe cars) could become something else, they could be something much lighter and much more purposeful, but by not having such a kind of a heavy influence from the past,” he says.

Perhaps much of this difference in car cultures also comes from the modern way that we live. Since the early days of the automobile, cars were always a chance to escape, to visit far-flung places that were less dense and urban, and in such places, roads provided an opportunity to enjoy the thrill of speed. With speed came the need for focus and cars that could handle corners more predictably. However, in modern China, where most people live in dense cities with grid-like layouts and traffic lights aplenty, speed and handling come second to comfort and utilization.

“We care more about how to give people a nice spacious seating experience rather than just giving them a sort of compact, very weight-balanced cockpit,” says Zhang. “I think being a designer you need to really think in advance and also to put yourself in the shoes of a customer, not always design like a petrolhead. If you always put yourself in a petrolhead mind, you will be left behind.”

Indeed, modern-day China is not unlike modern-day Europe and America. Urbanization is a global phenomenon and every day millions of people across the world sit in traffic jams, yet many Western cars are still built to the principle of freedom of movement rather than the way they are used daily. Streets get more crowded yet cars get bigger and bigger. With these contrasts comes opportunity.

“There’s a saying in China: We say, ‘Change the lane and try to overtake’. I think the world is changing but if we really look forward and far I think maybe what we’re doing here in China, we have a better chance. I believe what we are doing here is what people really want,” says Zhang.

Inspiration from unexpected places

“You have to be open; you have to be able to absorb any kind of information so I try to make myself sensitive to all the new kinds of information,” says Zhang when I ask him where he and his team find their inspiration. “No matter it’s the political, the economy, art, architecture, graphic design, or what is popular in fashion, I try to follow all the latest information.”

Indeed staying abreast of the latest developments will undoubtedly lead you to the contentious development of artificial intelligence. While examples such as chatbots and Netflix algorithms have become more or less a background part of daily life, the recent developments of platforms such as ChatGPT have reignited debates around its use.

For many creatives, the discussion has been around whether artificial intelligence is coming for their jobs, but that’s not a concern shared by Zhang and his team, who have been looking at the technology with some interest, more recently collaborating with universities and Microsoft Asia to see what it can do.

“What we could achieve right now (is that) AI could design rims for us,” says Zhang. He goes on to explain that AI needs to be fed with hundreds of thousands of images to learn from but that it’s not yet at a level to design car faces. But rather than fear for his job, Zhang sees it merely as another tool in a designer’s armory, much like digital editing software.

“I still remember back to 20 years ago when I first learned Photoshop. At the time that was regarded as something new. Normally we would spend one or two days to do one picture, but with the help of Photoshop, one click, done, that’s the efficiency we are talking about,” he says.

Growing family

Like most traditional Chinese auto brands that have begun to venture into electric cars, GAC recently decided to form a new brand for their EV offering, AION. The first EVs from state-owned brands tended to be electric powertrains shoehorned into existing models with the only cosmetic change being a plastic cover where the grille once lived, but the need to clearly define one from the other has risen in recent years as EV-natives brought exciting new designs to market.

Zhang’s team also needed to navigate this brand separation and eventually settled on two design studies that simultaneously give each a strong identity and somehow reflect the world we live in today.

“For GAC Motor we studied the history of it (and found that) it comes from the industrialization, the beauty of a mechanism, and it just needs to evolve when you get new technology. (For AION) we are more looking to the future and using EV technology so being eco-friendly is a key…not as something weak or not as something too soft but still with power.”

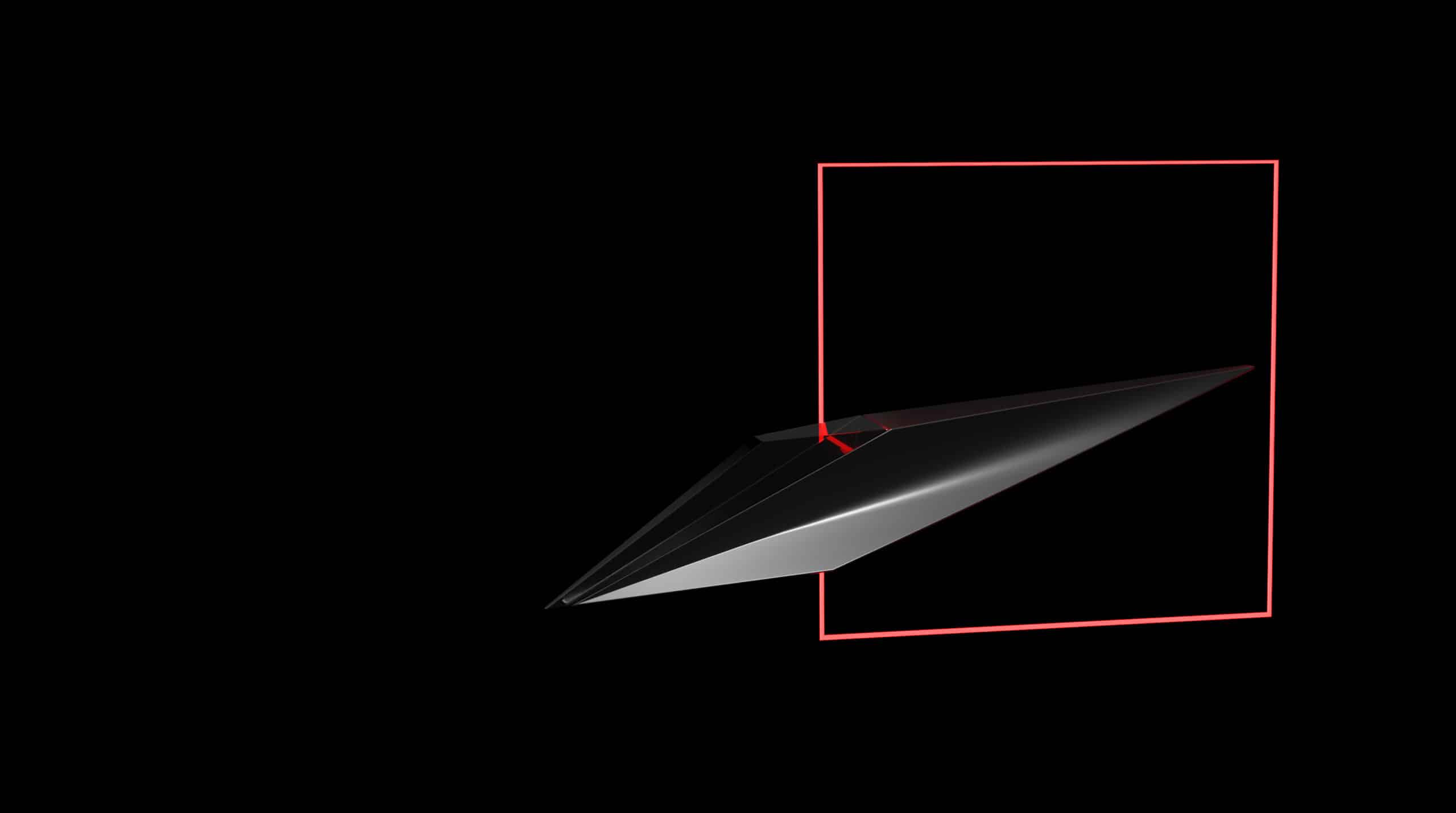

The philosophies also somehow reflect cultural differences between East and West, the more brutal, industrialized vision of GAC reflecting the ideology that “humans could conquer the world eventually, I think mainly from Western philosophy.”

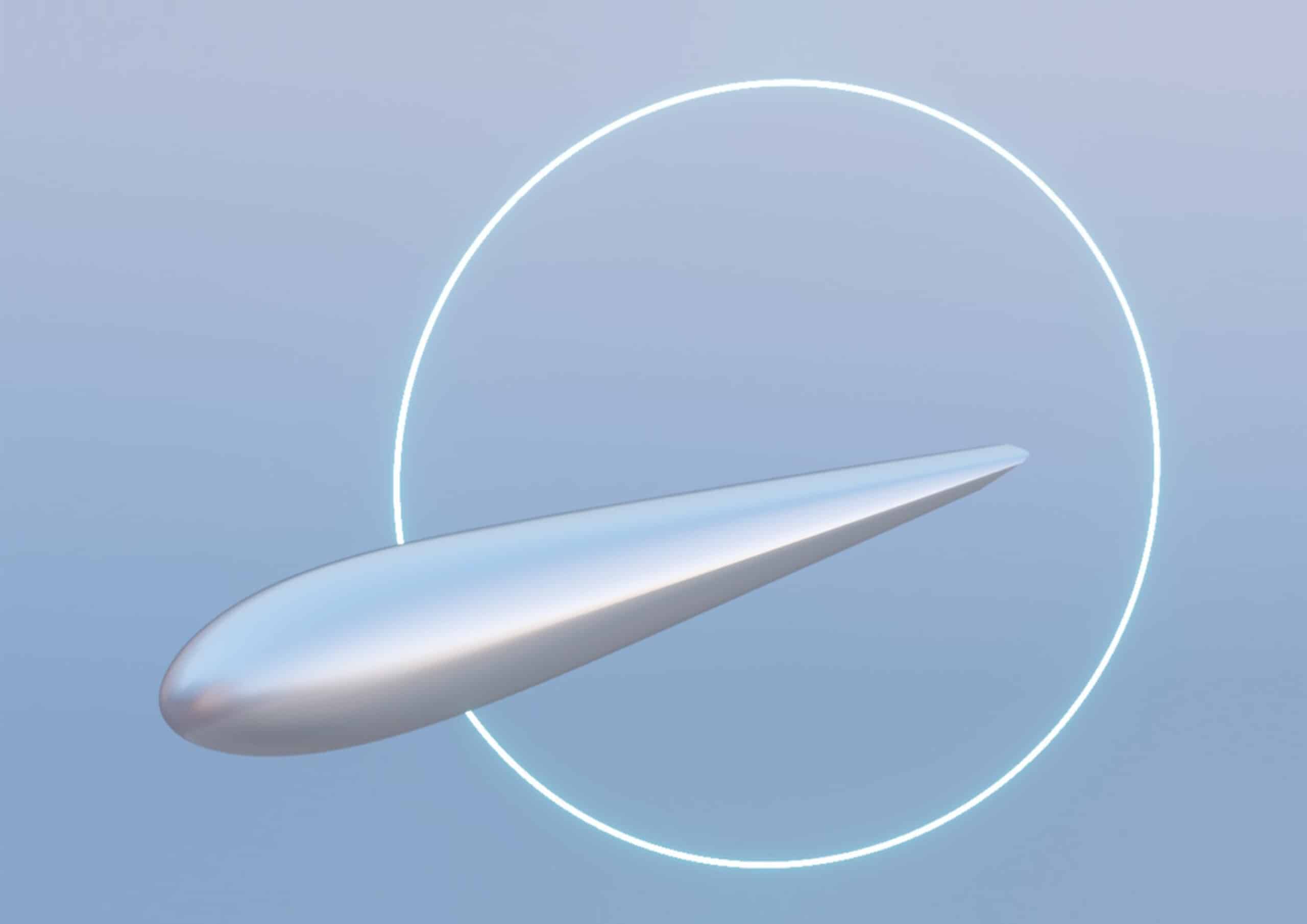

On the flip side there’s AION, reflecting the idea that “humans could adapt to the world, we don’t seek to change the world, but we seek how to get adapted to the world. This mainly comes from Asian, kind of Chinese or oriental culture,” says Zhang.

Indeed, the push to create a world where we produce less waste and do less harm to our natural environment is very much the antithesis of the past two industrial centuries.

For each brand, a sculpture was created that symbolized the design language. “We took a diamond as an icon as a symbolic image for GAC and we took the water drop as a kind of an image for AION.”

The future of design

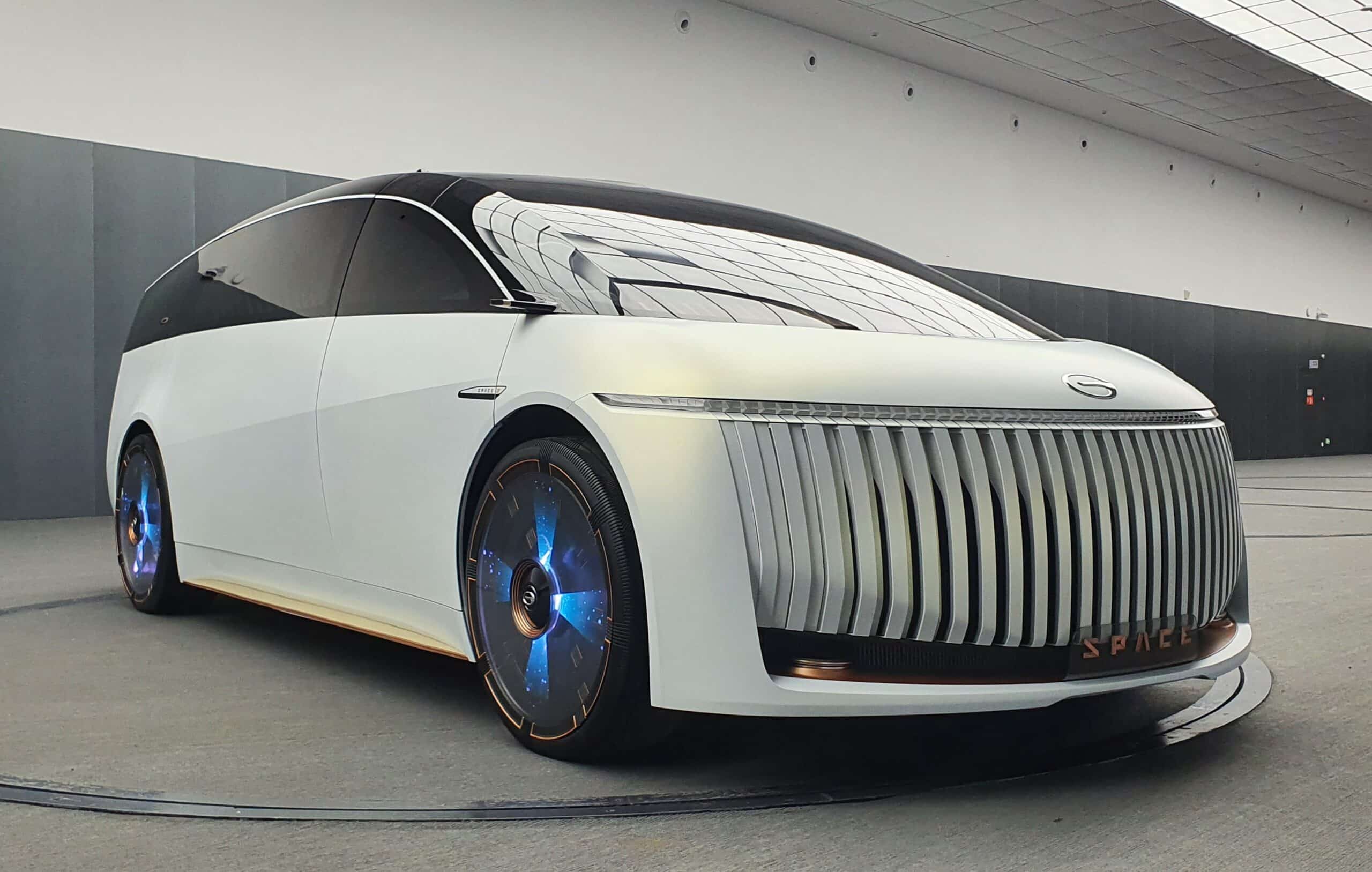

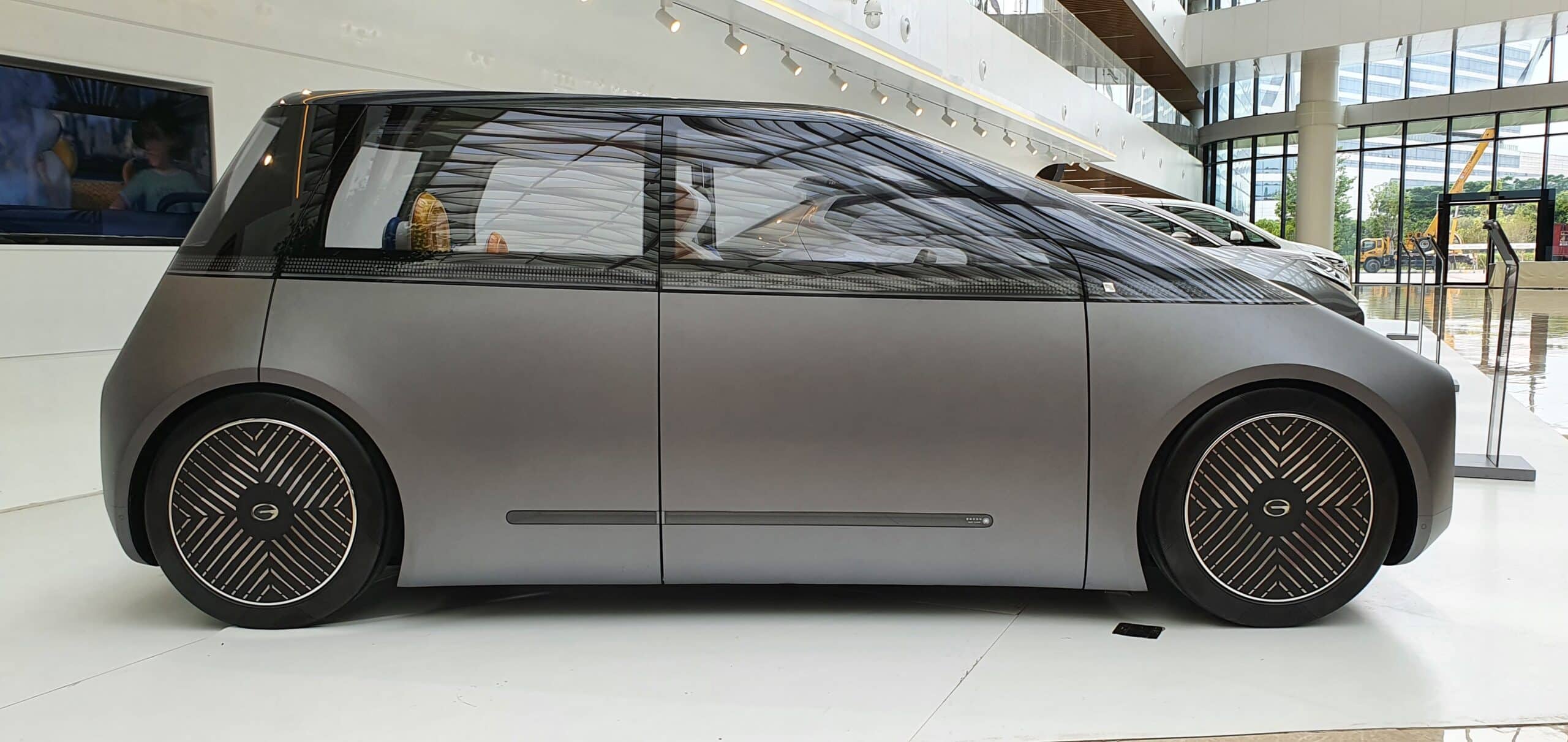

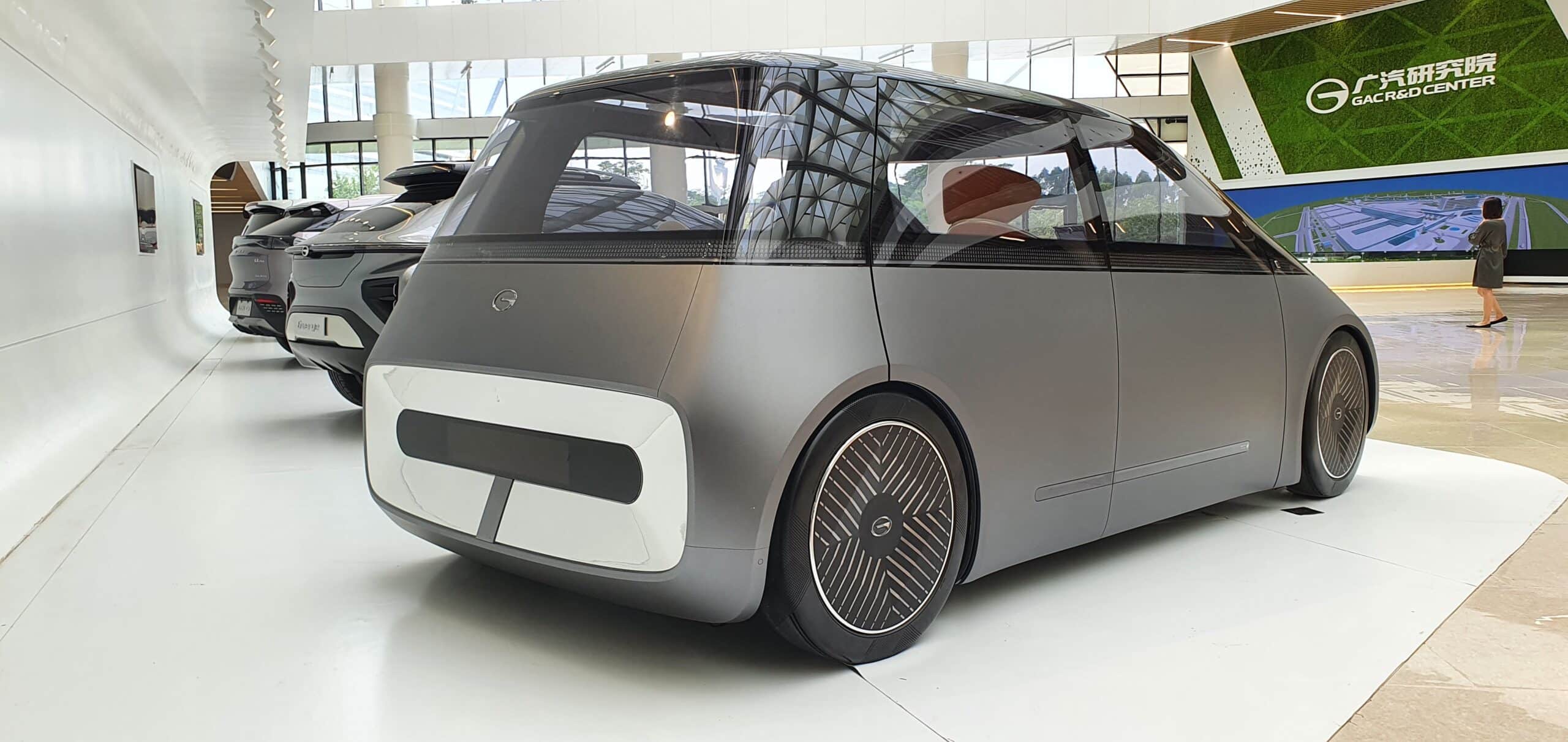

Of all the state-owned brands, GAC has perhaps been the most willing to embrace concept cars. Once a frequent sighting at auto shows, tightening budgets across the industry have reduced the desire for gratuitous design studies that rarely offer anything to the production cars that follow, but for GAC they remain an important part of the design team’s work, although now they must offer more meaning.

“At the beginning maybe, they were just purely a designer’s guilty pleasure, (but) as a design management…we need to assign more meaning and also commercially we need to bring more value to those concept projects,” says Zhang.

But what purpose can a concept car actually have?

“In the international car business, being able to create is a very important ability that means you have the vision and ambition for the future. Secondly, concept cars are the weapon or the tool for us as a design organization to test the water into the future.”

For GAC, it’s clear that lessons have been learned from the concepts they produce. For example, the learnings from the ENO.146 concept into aerodynamics have directly impacted the AION Hyper GT car. The concept achieved a world record low drag efficiency of 0.146Cd, while the production Hyper GT achieved a world record for a production car of just 0.19Cd.

ENO.146 also showcased the brand’s ideas around the concept of a family car, ‘family’ in China traditionally encapsulates “a typical three generations, six members Chinese family – two kids, one couple with two of their elders”, and these ideas were also applied in the AION V and AION LX models.

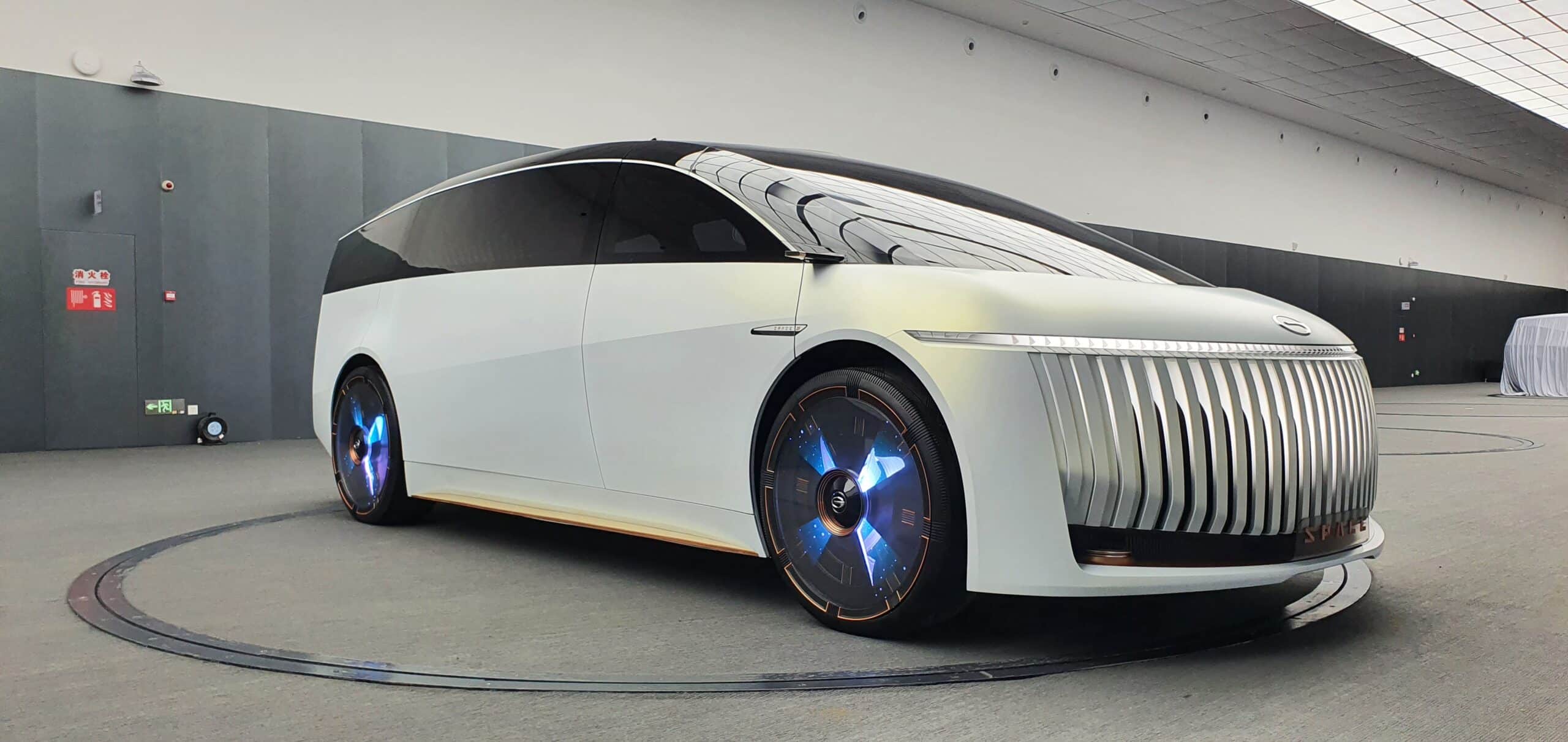

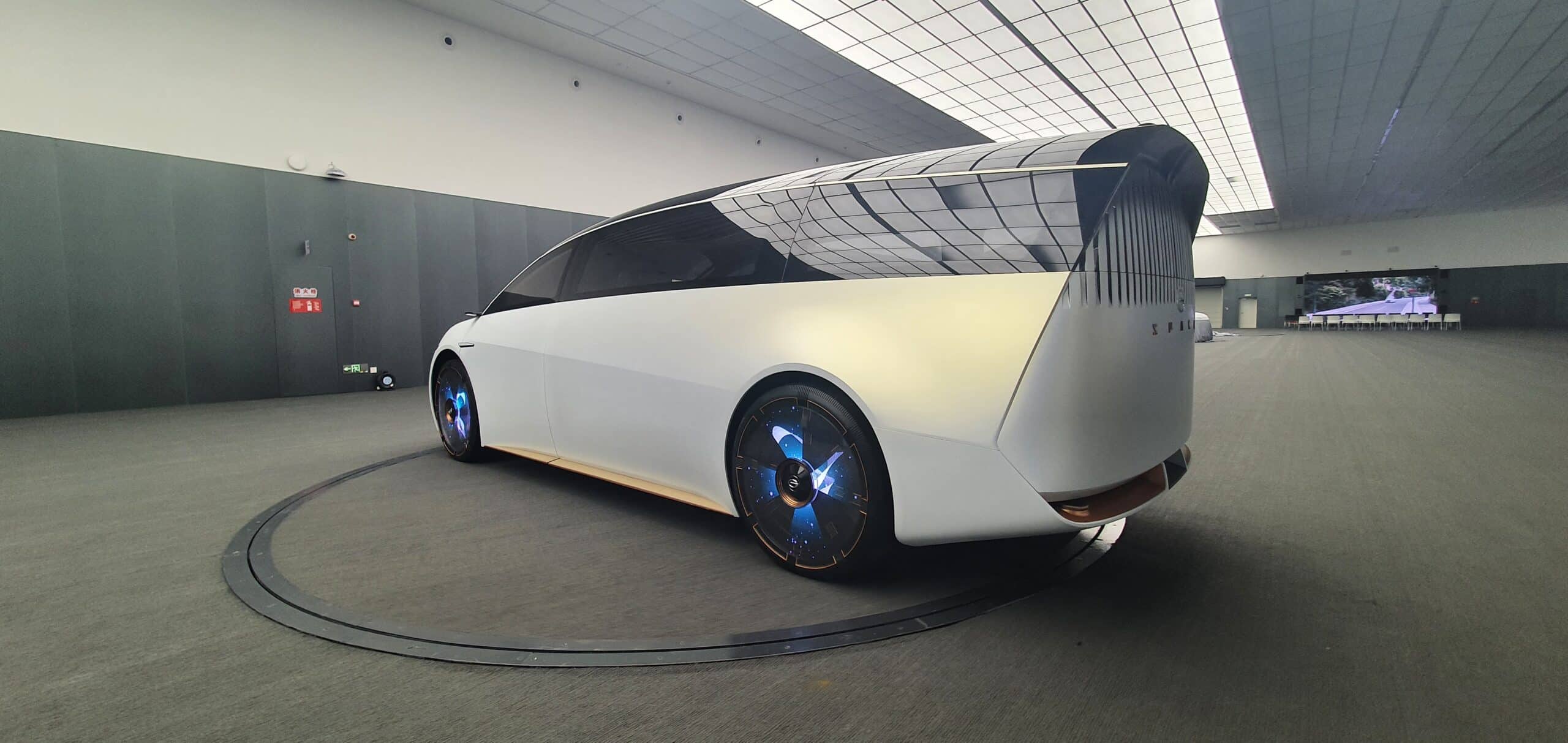

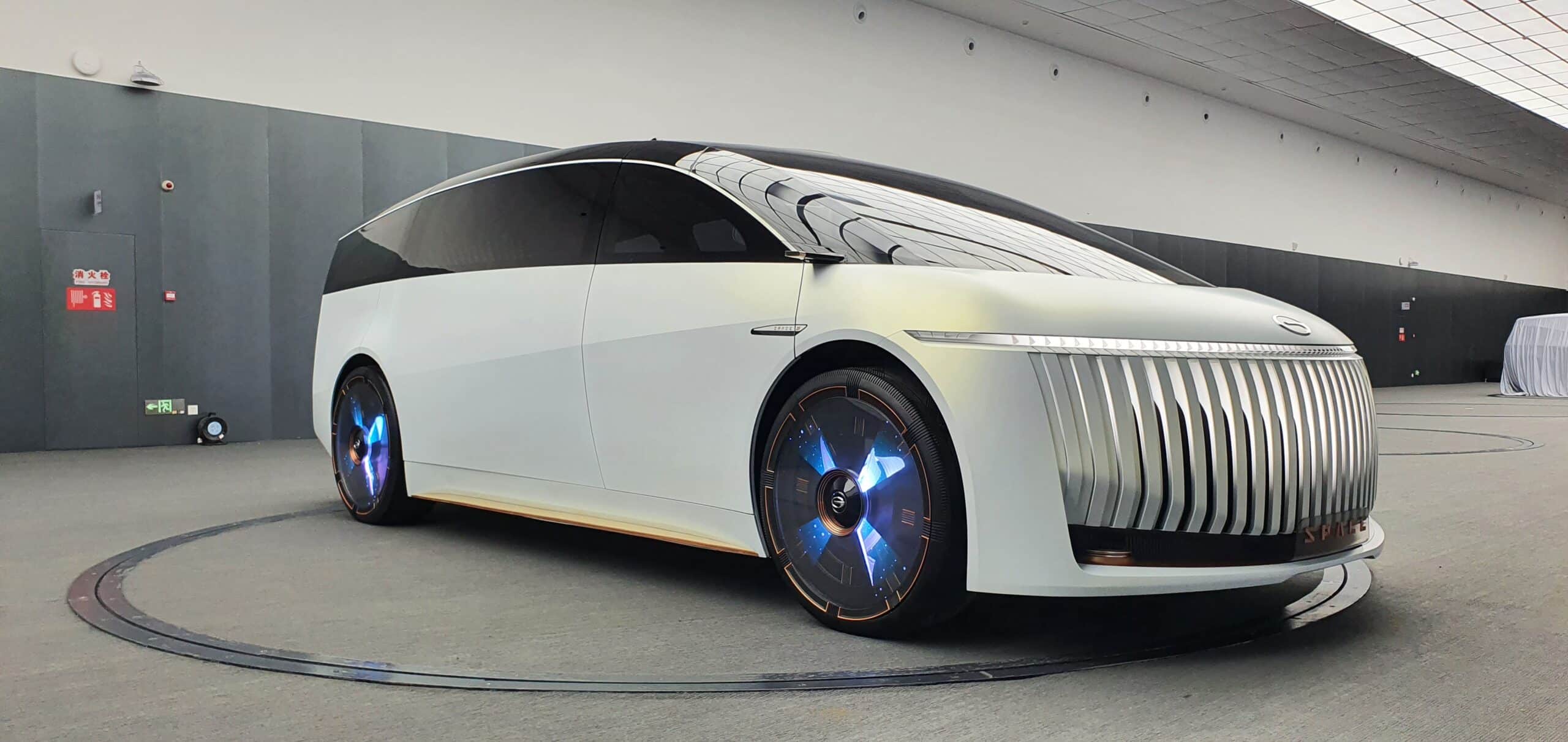

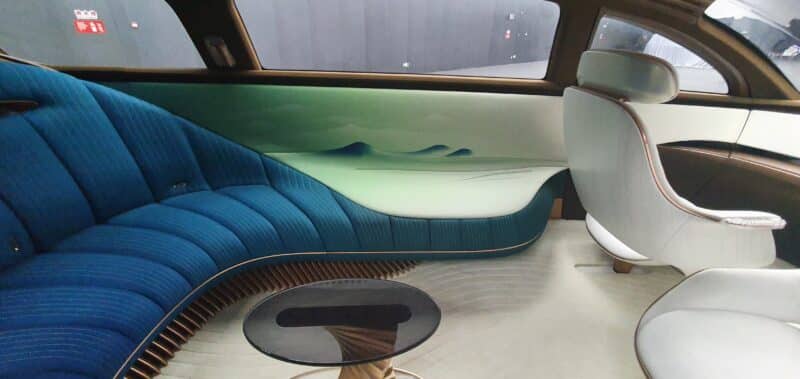

For other concepts, such as the outlandish but stunning TIME and SPACE concepts, the relation to production cars is a little harder to define, but both exhibit the concept of beautiful interior spaces that place more emphasis on the way a car is used and the comfort once inside, a trend which is expected to take more prominence in a world where autonomous driving becomes more common.

“For the SPACE interior, we were exploring (how) when the car is in autonomous driving modes, how the space is meaningful to a human being. Many others we’ve seen are like a box,” says Zhang, adding, “(In SPACE) we have put in a lot of very, very interesting ideas like the seating, the wooden strips with waves, and then hiding some kind of lighting inside and then the sofa. I told them, the young designers, you have to create the most comfortable sofa in the car ever.”

Indeed some of the more cosmetic elements of the SPACE concept have made it into the production M8 MPV, which features graphics inlaid into the wood on the dashboard that depicts the scenery of southern China.

So will we ever see something as bold and outlandish as the SPACE and TIME concepts hitting the roads?

“From now on you will see more and more GAC products coming out and I hope each of them will be as bold as a concept. (Maybe they won’t look quite like SPACE and TIME, but) give it a period of time and put all the products together, you’ll see how much progress they have made and how different they could be to the other brands and to the conventional cars.”

If the progress in China’s car design over the last 30 years is anything to go by, the next decade may just be one of the most exciting yet for Chinese design.

Read Also:

The story of GAC: Guangzhou auto industry before GAC

Mark Rainford is one of the leading English language authorities in the Chinese auto industry. You can follow him on Twitter.